Trigger Warning: This blog article includes outdated language to identify key moments in history and briefly mentions the affiliations of Hans Asperger.

What is Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)?

Think about our brains as computer operating systems. The norm, neurotypical, is Apple. Autism, and neurodiversity, is Android. Neither are better or worse, simply different. Both are equally valuable.

It’s an analogy the autistic community has been using to explain the way they interact with the world. Autism is often painted as a tragedy, or marketed as a superpower, but really, autism is neutral.

As the years go by, we’ve seen perceptions change and evolve, and we’ve watched accessibility start to take precedent in conversations around labour, education, transport and lifestyle.

So, what’s changed and why?

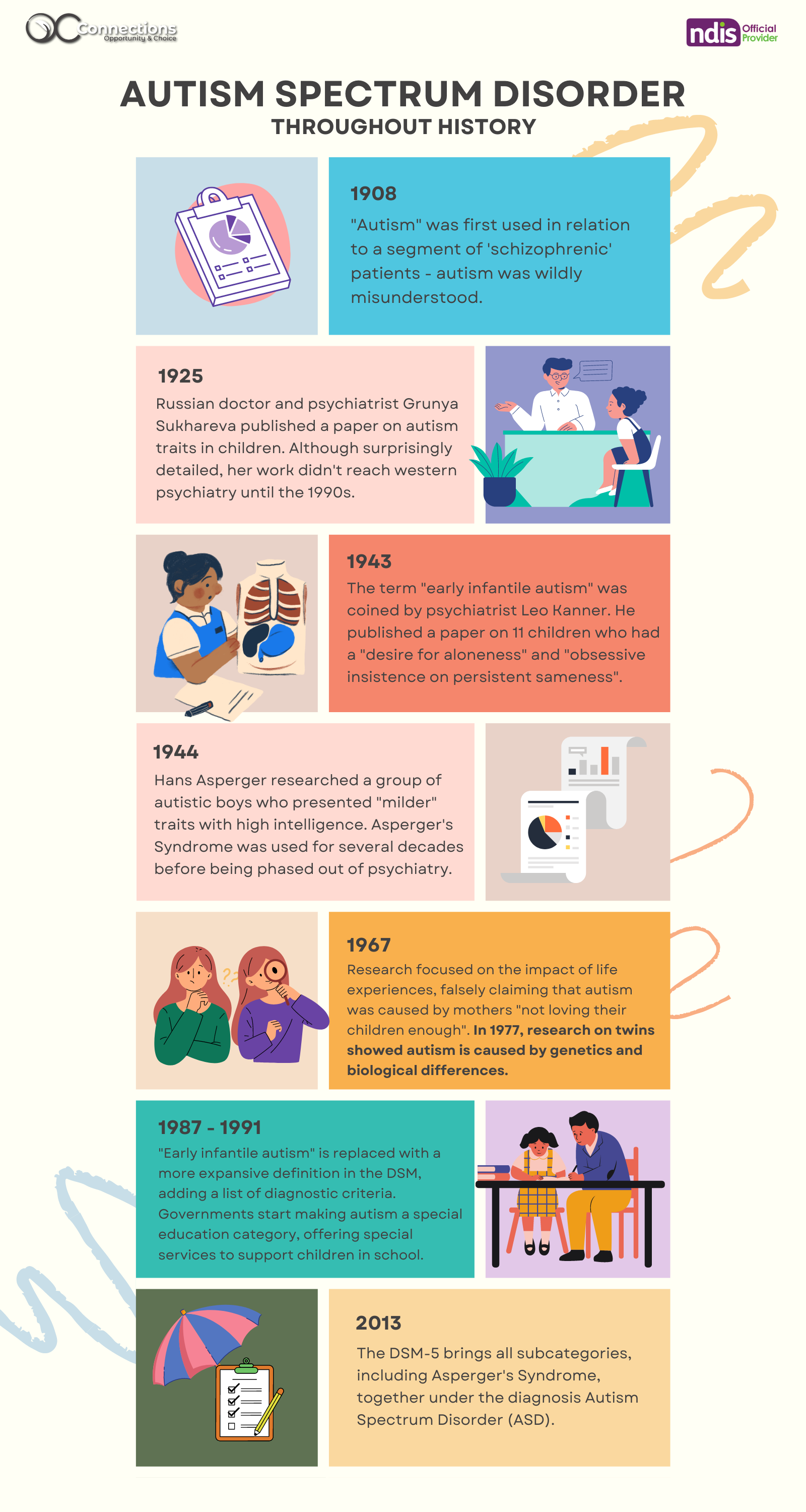

1900s

Before the turn of the century, autism and neurodiversity didn’t exist – in fact they were seen as, what we would call nowadays, mental health issues. The first major move away from classifying autism and intellectual disabilities as ‘spiritual acts’ of rejecting the norm was in the 1920s.

1920s

The first major breakthrough was in Russia in the 1920s, and although the paper published by Grunya Sukhareva didn’t make it to the western world, her impact on psychiatry did. Sukhareva identified many key attributes of autism based on her work with over 1000 children. It’s believed that Sukhareva’s findings were used in Germany in the years following, however she was incorrectly cited and her name was left behind. This research paved the way for Hans Asperger and Leo Kanner, two of the most well-known names attributed to autistic history.

1940s

The well-known Hans Asperger conducted ‘research’ on several young boys with, what was seen as, low-need, high intelligence autism. Based on inhumane treatment of autistic children, Asperger’s Syndrome was created. While Asperger’s Syndrome was adopted by the medical community for many years, it has since been proven that Hans Aspergers was directly linked to the Nazi belief in ‘gene hygiene’. Simply, he didn’t research to understand, he researched to erase. This was sadly the case for many researchers at this time, as autism was still wildly misunderstood as behavioural instead of biological. Leo Kanner went down a similar route, adding little insight into autism but coining the term “early infantile autism” which is no longer used.

1960s

Neurodiverse traits were seen as medical problems, things that needed to be fixed or removed from society. People looked at neurodiversity through the lens of pity, believing that people with psychosocial disabilities were ‘perpetual children’ who needed to be separated from mainstream education and work. Autism partially existed, but there was confusion as to what it meant and how it impacted community. Society was viewing neurodiversity as a burden, and many people with disabilities were placed into nursing homes and left behind.

Much of the research conducted in this decade was based on life experiences, viewing autistic people as traumatised individuals who were isolated due to a lack of motherly love. This harmful ideology only lasted a decade, as research on twins in 1977 proved autism is caused by genetic and biological difference.

1980s & 1990s

The DSM-5 adapted their definition of autism, adding diagnostic criteria based on new scientific information. Federal governments, including USA, UK and Australia, started to identify and provide special services for children with autism in school. Awareness was growing, and so was inclusion.

Early 2000s

Barack Obama removed the term ‘r*tardation’ from all federal records in line with “Rosa’s Law”. In 2014, the diagnostic manual evolved, blending different branches of autism (such as Aspergers) into one ASD umbrella diagnosis.

The linear scale of high-functioning to low-functioning autism was dissolved and replaced with a multi-level, person-centred spectrum of characteristics and traits. Functioning terms were phased out because they were incapable of defining the complex and diverse challenges autistic individuals face. Diminishing the impact of autism only perpetuates stigma and makes it more difficult for individuals to seek disability support. To include people with disabilities in society, we must see them as more than their diagnosis, more than the sum of their parts – as complete humans with valuable life experience.

Present

The first Self-Assessment of Autistic Traits, by and for autistic adults, was released in 2022*. It’s different from mainstream diagnosis because it identifies the impact masking can have on our views of autism, and it simplifies confusing language into clear, straightforward statements.

The current diagnostic criteria for autism works well for some of the neurodiverse population, however it doesn’t take into consideration the societal conditioning that many undiagnosed autistic people go through. The way we are raised, the schools we go to, the friends we have – they all impact the way we view autism, however the views aren’t always accurate.

It’s hard to know that you think differently to the norm when the way you think is all you’ve ever known. The Self-Assessment separates ‘traits’ such as lack of empathy and missing social cues, into clear statements presented as thoughts. Some examples are:

- I prefer to follow a routine.

- Transitions are hard.

- It’s hard for me to notice what my body needs,

- I process things much better one sense at a time.

It can be easier for autistic people to understand thought-based questions opposed to action-based, as conditioning can impact the way we understand our processing, urges and behaviours.

Social media has played a vital role in autism awareness and acceptance, particularly for people raised female. Rates of diagnosis are increasing because diagnosis is becoming more accessible. On TikTok, women are sharing their stories and experiences. People who have struggled their whole lives and didn’t know why are finding answers and joining communities.

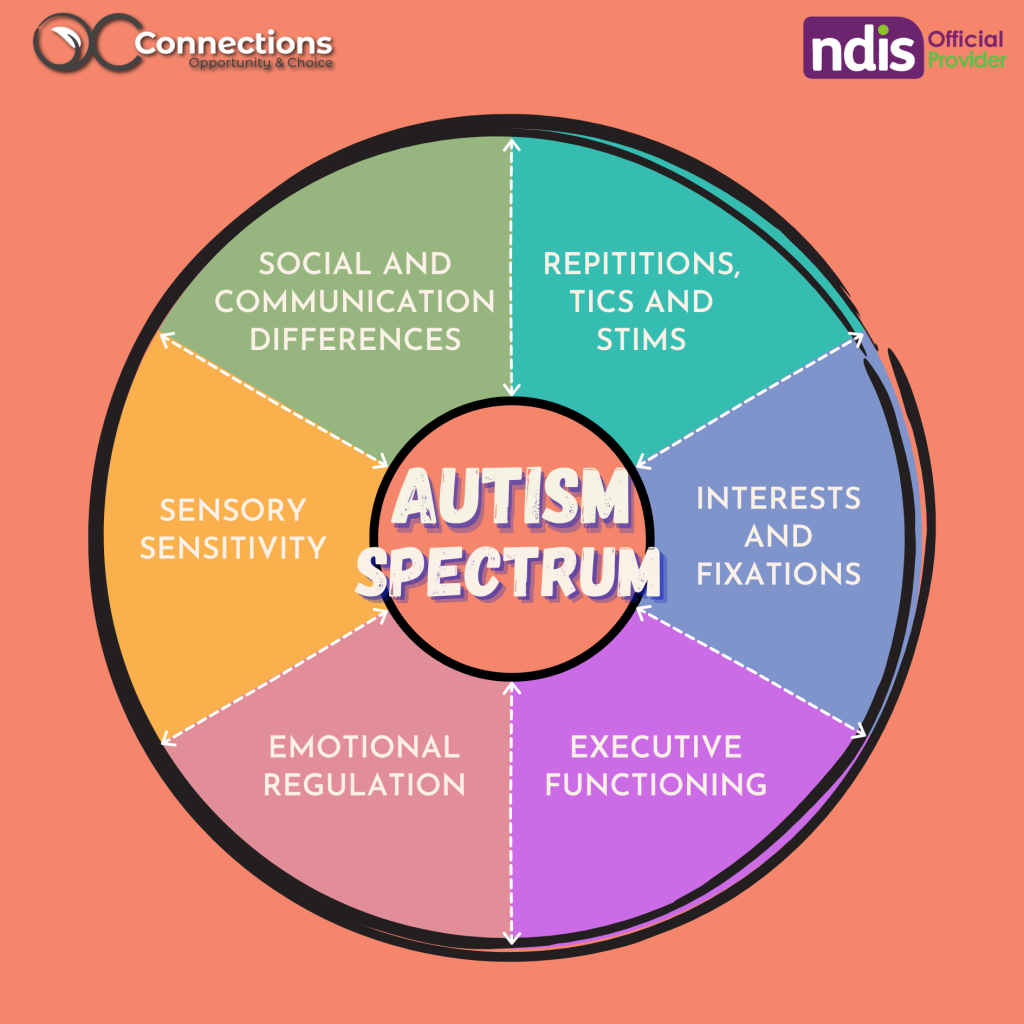

The autism spectrum has been reimagined and now looks something like this. Traits will differ depending on location and service – for example, eye contact and motor skills are also sometimes used as diagnostic criteria.

Not everyone is on the spectrum, only autistic people are. It’s a common misconception that everyone is “a little autistic” or “a little ADHD” when that is not the case. The myth dismisses neurodiverse experiences and minimises the struggles they go through in learning, work, and social life.

Defining autism is important because, for a century, autistic people were excluded from community in almost every facet. Neurodiverse people face daily challenges participating in the world, and those challenges deserve to be heard, understood, and supported.

The Future

We’re learning so much, and have come so far, but there’s always more work to be done.

Unemployment rates are growing for autistic adults. People with autism, intellectual or developmental disabilities, ADHD, downs syndrome – all segments of neurodiversity – want to work, and around 50% have the necessary skills to start work immediately. With Australia’s labour force hitting new levels of understaffing, it’s crucial we improve disability inclusion.

Only a third of neurodiverse people will go on to complete tertiary education or post-secondary training, compared to around 50% of Australia’s population without disabilities.

Government funding isn’t where it should be – even the Minister for NDIS, Bill Shorten, has agreed that the disability scheme needs an uphaul. He says that, due to short-term planning, NDIS participants have to ‘repeatedly prove their disability’ to continue receiving adequate care^.

People living with disabilities report that discrimination is an ongoing issue, particularly in housing, healthcare and employment.

The neurodiverse and disabled community are still fighting for change and inclusion. Advocacy and education will help to open doors and pave the way to a better future, just as it has for the last century.

What changes do you want to see?

Links:

*Ratto et al, Self-Assessment of Autistic Traits, https://pure.port.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/61113719/Centering_the_Inner_Experience_of_Autism_Post_print.pdf

^Evans, J, NDIS ‘reboot’ will include more staff, cost crackdown, longer-term plans and shonky services purge, Shorten says, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-04-18/shorten-outlines-ndis-reboot-fraud-crackdown/102236386